I get a huge number of questions from web developers wanting to know exactly what happened to the Web Intents. This is my recollection.

I don't feel bitter; I am just disappointed. It was my first big project failure and at the time it hurt when it got canned.

About 6 months ago I sent an email to the DAP — the working group that was one of the hosts of the Web Intents task force — that I think should be shared more broadly.

This is my personal reflection on what happened and I know a lot of people have different recollections and feelings about what happened and I think I am probably glossing over a lot of the facts (it's also been a while since it happened so my recolection might have changed).

TL;DR

The UX that killed it especially on desktop, we hit a huge number of problems and the choices we made designing the API that meant we couldn't solve the UX issues without really changing the way we built the underlying API and by the time we realized this it was too late.

There are a number of things that compounded the problems the API faced.

- Timing

- Use-cases

- Lack of focus in the "intents"

- An <intent> tag too far

- The ecosystem was hard to build and we solved that part of the problem too late

- The API affected the UX

- Stubbornness

Why was the timing bad?

What is the most important aspect of a joke?

_I don't know? what is the most impor… _Timing … tant… Oh I get it.

We didn't know this at the time, but in retrospect we were aiming for the wrong platform first and we were designing on a platform that didn't naturally fit the API. Desktop.

Desktop is huge, but we were at the peak of the bubble. I am trying to remember if I, or the team, actually knew at the time that Chrome on Android was "a thing" but I am pretty sure it wasn't broadly known on the team I was working on.

It is pretty clear from the terms we used "intents" is that it was heavily inspired by the Android intents platform. In my original demo the name was as far as it went. When we started the project officially we went a step further and aligned methods and objects very closely to the Android platform. In retrospect this didn't actually make sense, Activities don't exist on the web, but we had an API called `startActivity`.

The majority of this is down to me, I managed to convince the team that in the future it would be easier to win support for integrating into Android if we reduce the number of changes that were needed. My "grand vision" was to have apps on the web to be as powerful as apps on Android. A web page could be launched by a native app or web app and the user would have a seamless experience from app to web-app. They wouldn't even know they are dealing with the web. In my head to do this we needed to be almost "API compatible" with the Android ecosystem.

In hindsight this had a strong benefits:

- Every Android developer would just "get it" so we could training a large number of developers would be easy.

- If the Android Browser (it was WebKit based and Chrome was WebKit based) ever ported Web Intents it would have been incredibly easy to map.

But it also had a number of rather significant drawbacks.

- Developers would feel like an Android'ism was being pushed on the web.

- Other browser vendors and groups at the W3C felt it was too Android specific (see Stubbornness later)

I learnt a lot about winning support and influencing people. It turns out naming an API the same as a platform feature doesn't always guarantee success.

What use-case did Web Intents solve?

General inter-connection of apps. A lofty goal.

We didn't specifically solve a single use case well other than connecting apps. The broad verb-space meant that a lot of developers wanted to design their own actions. I believe that this diluted the message of intents, and is something that if I had researched the Android ecosystem more effectively at the time, I would have probably constrained the verb eco-system to a couple of small but well defined cases:

- User X uses Twitter and wants to attach a picture directly from their Google drive, Dropbox or preferred provider.

- User Y wants to view document A in their preferred app

- User B wants to edit object F in their favourite editor

- User A wants to share a link to their favourite social site

By solving the common user problems we could have iterated on the UX more effectively and it might have even led to a different API design. We just simply didn't explore the idea.

Lack of focus. How does that work?

We were overly broad in terms of intents: We started with a lot of custom ones that we thought were cool, and I tried to encourage developers to think of new ones. The lesson I learnt from this is that we should have started with a very small pool with no ability for developers to deviate and lead them through to solving very specific use-cases with the API. In the project we were far far to late in trying to constrain the platform and guide developers in a very opinionated way.

An <intent> tag too far. Why does wanting an <intent> tag cause so much consternation?

See stubbornness ☺

There were two major aspects to web intents:

- User Agent Discovery of services

- User invocation and selection of services.

We were pretty keen to have a declarative way to describe the services and actions that a site can offer to users and to have this inline in the HTML.

My long term vision was to have search (any search engine, not just Google) have a massive index of functionality, I mean imagine the power of web of actions on objects. Rather than searching for the name of an application you could say "I want to edit images", and boom, a list of apps that edit images.

I am very surprised this still hasn't happened and I do still think it is the next frontier for app discovery. (I am writing this after I see pinterest doing app install buttons; pins are a small social discovery mechanism yet there is no user intent).

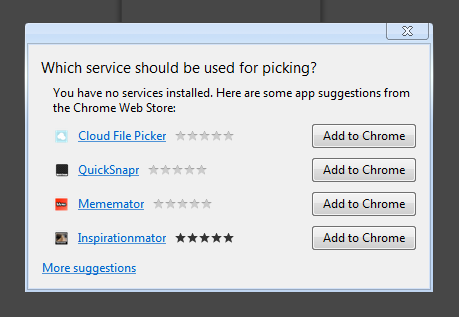

We actually got pretty damn close. The Chrome Web Store could index app functionality and it would offer the user the chance to install an app if you didn't have something that could handle that functionality.

The <intent> tag though cause a huge amount of consternation in the specs groups. Many people were outraged that we wanted to add a new tag (especially in the head) and we were quite stubborn in our insistence in having it. In hindsight, suggestions that we ignored such as a Web Manifest and <link rel> were valid solutions, and in the case of the manifest is now in Chrome (sans service discovery) and Firefox and would have been the best place to put this "intent" declaration. The irony being, we only ever consumed the Chrome Web Store manifests intent declaration.

Personally, I think I felt it was the purest solution and we would receive kudos for getting a new tag into HTML and I think that blinded me. I can't speak for the rest of the team on this though.

Ecosystems are hard. Where is the value triangle?

This is one of the biggest things that I learnt, especially in relation to Developer Relations.

There were two problems for developers with Web Intents: Services need clients and clients need services, and our ecosystem was in the middle.

No matter how great the API if you can't fulfil the demand on either side of the equation all you have is an API.

I remember the day that I realised this and I pitched to the team that Chrome should solve half of the equation. If Chrome fired an intent (such as 'View') then a clear consumer market would be created immediately. If Chrome could handle an intent then there would be a market for producers. For the longest time, Chrome was the middleman without any customers.

Usage of Web Intents increased dramatically when we solved one side of that problem by adding in the ability to "VIEW" RSS feeds in your preferred apps. It drove a huge number of installs and made it simple to demonstrate that the concept has value to other RSS readers who wanted to be able to offer their experience to users.

In principle this was a sound idea, the problem we faced is that RSS is sacrosanct to the community and even though Chrome never handled RSS well, we came in and disrupted the way it worked and didn't let developers fall back to the original methods of Chrome. The community was vocal against this move (I believe it was one of the highest started bugs in the shortest amount of time on crbug.com.

The API affected the UX. How does that happen?

You learn a lot as you develop software and interact with developers. This is a good thing, developers tell you the things that suck, the things that work and as long as you provide value and you listen to them.

I didn't appreciate at the time.

One example: Android has a modal full screen (in most cases) stacking app context. Desktop web doesn't. We had a huge issue with "what happens when you kill off the app that initiated the action" and given that we were pushing people to use "EDIT" intents where all the work is done in the app that fulfills the intent yet have the initiator save the data, if that closed the user was hosed. We stuck with this model, I ignored feedback and ultimately a lot of the feedback we got when the project was killed was "The UX was terrible" and it was the insistence on designing an API that has async task but wasn't async on the platform we cloned the idea from.

If we had thought about where it would be used, we might have designed the API differently or the interaction model. All I know is that the API affected the UX.

Stubbornness affected collaboration

In retrospect, I also think we were overly stubborn in our interactions with Mozilla and other browsers, right up until we decided that they had some good points by which time it was too late. We were also working with a some of the wrong people in Mozilla to start with which delayed things in my opinion, but that is not that important now.

Suggestions came in from good people at Mozilla, and for me, my stubbornness blinded us. Ultimately this meant that Mozilla in Firefox OS went and implemented Web Activities that solved a lot of the problems that we thought weren't problems.

This is my biggest regret.

We know we need to solve the problem. Now what?

I have a lot of thoughts about how a "new" project should run and I am worried about talk of MessagePorts via `navigator.connect` (they add huge complexity for developers at a time when they don't need it, or it is not clear) without specific use-cases. I also see the same thing happening in "WebWishes" which is (was… I have not checked it out in a while) looking at things in a desktop only way and at just an API level.

I would love us to document all the types of actions we know users are struggling with (for example, I know a lot of people just want to view files in their preferred web app for data that is held locally to them and registerContentHandler right now requires a server won't work offline at the moment) and then go from there.

Right now I see: Single shot (a calls b with no data return), Returnable (a calls b, with data being returned), Long-running Chatty (MessagePorts etc). I strongly suspect the API surface and the Usecases for each of these is different, but I think even this is too far into trying to solve the problem.

I would like to see:

- A list of use-cases that we need to solve to help users

- A constrained list of actions that we think are critical (based off use cases) to help developers solve the problem

- Thought on where these could fit into the existing platform (i.e, the pick intent we had, why was that not just part of input type="file"….)

- I would like us to separate out discovery of services a site can offer (i.e, manifest or intent tag etc)

- I would like us to separate out service resolution and selection

- There is actually a lot more that I need to think about.... still.

p.s, I am happy to get back on this and help out as much as possible, but I would also need to get broader support from the Chrome team again on this.

To be continued: Now that Service Worker has landed, I have started prototyping the next generation. :)

I lead the Chrome Developer Relations team at Google.

We want people to have the best experience possible on the web without having to install a native app or produce content in a walled garden.

Our team tries to make it easier for developers to build on the web by supporting every Chrome release, creating great content to support developers on web.dev, contributing to MDN, helping to improve browser compatibility, and some of the best developer tools like Lighthouse, Workbox, Squoosh to name just a few.

I love to learn about what you are building, and how I can help with Chrome or Web development in general, so if you want to chat with me directly, please feel free to book a consultation.

I'm trialing a newsletter, you can subscribe below (thank you!)